Four Mississippi

A few seconds in the Delta

Those of you who know me a little are aware I have a superficial interest in the mound builders who lived throughout the midwest and south for many millennia before the Europeans arrived and killed them or put them on a death march to the plains. There are several mounds and Indian village sites along the rivers where I’m grew up. As a kid I walked the fields picking up arrowheads and sherds of pottery. I know people who got really into collecting artifacts. Or more realistically, looting. The excuse is that the artifacts were just getting destroyed by farming, so it was doing humanity a service by taking them. There was some truth to that, but the serious artifact hunters went way beyond walking the fields. Many of them were straight up grave robbers. Human skulls were prized. Valuable pieces of art and history lost to humanity.

For all those years the idea of going to Mississippi was kicking around in my head, it never once occurred to me to think about the mound builders there, even though I was aware that they were active throughout the south. I’d never thought particularly about the lower Mississippi River valley. Turns out it was the most densely populated area of mound building culture for thousands of years.

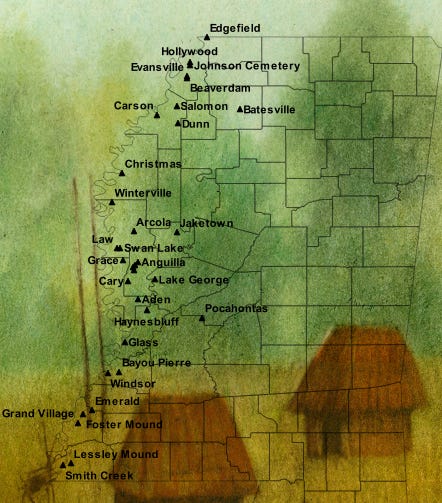

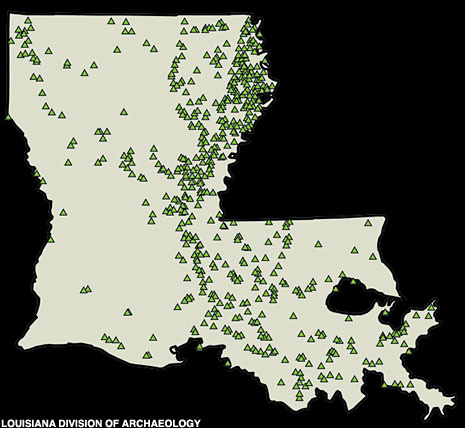

Although you can’t tell from the map of the marked sites above, Mississippi has the most mounds. Louisiana has over 700 sites, including two of the most historically significant. As you can see, this was a populated area going back thousands of years.

I recently read “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow. Graeber, who died tragically young, was an economic anthropologist and good old fashioned anarchist. Well, maybe not old fashioned. Perhaps it’s better to say he was a nouveau anarchist, one who somewhat brought anarchism back in fashion. He was best known for his book “Debt: The First 5000 Years” and for being a leader at Occupy Wall Street.

Dawn of Everything examines the question of whether or not our current top down social system ruled by police states and bureaucracies is historically inevitable. In order to answer that question, Graeber and Wengrow examine what’s known about archaic societies, essentially those that flourished before the Iron Age. A big part of the book is devoted to the mound building cultures.

So I was somewhat gobsmacked when I was at the Vicksburg civil war battlefield and asked a park ranger what other historical sites I should see in the area and he mentioned Poverty Point. Dawn of Everything uses Poverty Point as a prime example of how so much of what we have been taught about there being an inevitable progression from hunting and gathering to agriculture and industry is wrong.

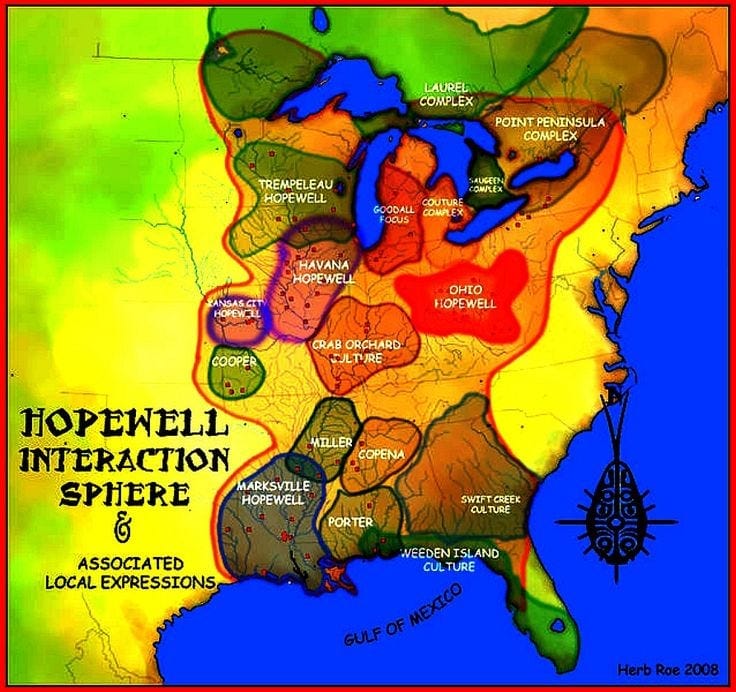

Poverty Point was a large ceremonial center for mound building cultures for roughly 600 years between 1800 and 1200 BCE. Look again at the map at the top of this article. Over 3000 years ago, for over 500 years, people traveled from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico to take part in some kind of ceremonial gatherings and who knows what else.

An important thing Gaeber and Wengrow accomplish is to make you see ancient peoples as intelligent. Just like us they had opinions about their societies, politics, religions, and the natural world. They were not passive hunters and gatherers with no thoughts but survival. They were bold explorers of two massive continents and intrepid travelers, going hundreds, perhaps thousands of miles from their homes to attend large festivals and trade. They enjoyed millennia of relative peace and freedom probably unrivaled in human history.

Unlike ancient pyramids made of stone, the mounds left behind by North American Indians are not awesome to look at these days. Most are just large piles of dirt that only a trained eye can distinguish from natural hills.

But although they are not much to look at, mounds contain interesting facts and mysteries every bit as fascinating as the Egyptian Pyramids. Emerald mound, for example, was made with over 315 million pound of dirt, which translates to over 4 million 75 pound baskets that had to be filled and carried and dumped and sculpted to create the mound, all at a place with a population that probably numbered in the hundreds. The mound builders had devised a complex system of measurement that was used across the entire culture. Many, if not all, of the mound complexes were aligned with celestial events that required hundreds of years of astrological observation to discern. How small bands of far flung hunter gatherers accomplished such feats if science and engineering and construction remains a mystery.

But is it really so mysterious? Observation, documentation, collaboration, exploration, finding meaning in the world, trying to figure out the best ways to arrange society – those are the things humans do and the people of North America from 7000 years ago were no different than us in those respects. Arguably, they were much better at it. For the most part they traded in knowledge more than material goods. For long stretches they had no empires or kings. Theirs was largely a cooperative society. They were as free as humans can possibly be, at least for long stretches. The real mystery is why we allow ourselves to live in empirical police states ruled by madmen these days.

But I’m much less interested in those kind of political mysteries than the more esoteric ones. The Don Juan books by Carlos Castañeda, particularly the third, were big influences on my life and outlook. Castañeda essentially created a religion out of Native American stories and borrowed ideas from other world religions to create a vibrant world that existed outside our normal perception. In Castañeda’s world, nature was populated by supernatural beings that had been driven to the most remote and beautiful places. Above and beyond the mumbo jumbo, he was able to communicate a sense of awe for the incredible beauty of the natural world as well as any writer, and much better than all but a few. I think being able to enjoy his stories and accept them as containing some kinds of truth while knowing they were entirely fictional greatly informed my outlook on life. Believing life has meaning and that supernatural forces exist is probably kind of dumb. Pretending to believe in them, however, can be very rewarding, and often sublime.

The Don Juan character often spoke of places of power. That’s something I always look for when I’m out on my little explorations. I’ve found plenty of places that seem to create powerful feelings. I’ve found many places that seem to impart a sense of awe and mystery. I’ve also found some that seem to radiate a sense of fear and dread. One would think that sitting on the neck of the massive 2500 year old giant Indian mound shaped like a bird at Poverty Point would inspire something deep and meaningful. I sat up there for a long time, cleared my mind and tuned into the natural surroundings as best I could, but felt nothing, at least nothing I wouldn’t feel sitting on any random hill in the country on a beautiful day. And that’s what I feel at all the mounds I’ve ever visited. Nothing. Whatever they once were, they are no more.