On Influences

Part 1 - Will Counts and the Distant Past

I’ve been watching The Story of Film: An Odyssey, a 15 part examination of film history by Mark Cousins, which should be called A Story of Film, rather than The, because duh, but that’s beside the point. In the first episode, and then throughout, he shows how an innovative shot from an older film influenced a shot by a later filmmaker. It’s usually described as an homage to the actual innovator. In most of those instances, if a writer were to do a similar “homage” to another writer it would be called “plagiarism,” but that is also somewhat beside the point. So what is the point? Hold your horses, cowboy. I’ll get to that.

Those “homages” delineate a clear break in film history – the advent of the film school. Once people started studying what had been done before, it was inevitable that one of the results would be a Canon, and like any Canon it would bear plenty of little dogmas, which is mostly what we see not just at the multiplex, but at the art house as well.

The greatest film artists still innovate within the Canon, but sometimes it seems to be more putting existing pieces of a puzzle together in different ways rather than making something entirely original . I am tempted to compare their method with how so many popular country music tunes are written with kitchen magnets. But instead of throwing terms like “pickup truck,” “tight blue jeans,” or “New York” at the fridge, they toss scenes from Goddard, Tarkovsky, Bergman, or Breton to build their narrative. But that’s a little unfair. Unlike pop country songwriters in Nashville, great filmmakers arrange the stuff they rip off in ways that enhance the meaning of the story.

Still, it kind of bothers me. The first I remember becoming aware of it was when I watched Paul Schroeder’s First Reformed while listening to his commentary. Schroeder, who is one of my favorite directors, is very upfront about how he lifts scenes he likes from prior films. He pops in and out of The Story of Film from time to time and they show how he took shots from other people’s work and put them in his own films. It’s not something he tries to hide, and that seems to be true with directors and cinematographers across the board – it’s something they readily acknowledge and take pride in. During the First Reformed commentary there’s a part where he says he was stuck so asked himself what Tarkovsky would have done. Then we see an actress floating.

The best and the worst of it for me was the Gus Van Sant section. Cousins shows how the walking scenes in Elephant were directly lifted from someone else’s work. Elephant is one of my favorite films and Van Sant one of my favorite filmmakers so I kind of felt like I’d been had. I thought Elephant was one of the more innovative films I’d seen, but maybe it turns out that such was not the case, certainly not to the extent I thought it was.

In Van Sant’s case particularly, I really shouldn’t have been surprised. The epitome of lifting scenes is his shot-by-shot remake of Hitchcock’s Psycho, which he talks about in one of the episodes, and which helped alleviate my concerns somewhat. He says that even a faithful shot-by-shot remake of someone else’s work cannot be the same because what matters most is the filmmaker’s intent and that cannot be copied. I see what he’s saying, but am still uncomfortable.

Still photography has also been changed by people studying it, but instead of film school it’s journalism school or art school that has defined the Canon and provided the dogmas. I recently watched a Master Class by Annie Liebowitz and it was good on many levels but one of the main things that caught my attention was the parts about her influences and what she was exposed to in art school. I’m from a j-school background and I found it interesting that we had such a common core curriculum.

My first photography teacher was Will Counts, who was about as old school as old school gets. He was what they call a real character who was always telling stories about the old days before such superfluities as light meters, flash, and autofocus. The old photographers would just pull up with their cars and light the scene with the headlamps, doncha know. He was caustically funny and regularly turned his wit on us poor students. I think it was the first assignment, I took a photo of a girl in a trailer park that I thought captured something profound about poverty in America. After each assignment, Counts would take our best picture or two and display it on a large screen and critique it in front of the class. I’ll never forget what he said about the girl in the trailer park photo. "Almost a good photo, but that tree growing out of her head must be really painful.” Everyone got a good laugh out of that, but their turn would come. Of course nowadays he’d be fired for that kind of thing, or at least reprimanded, but you can bet I never failed to notice trees sticking out of subjects heads again, at least not in editing. And it pains me to see all the people whose feet are cut off in so many photos almost as much.

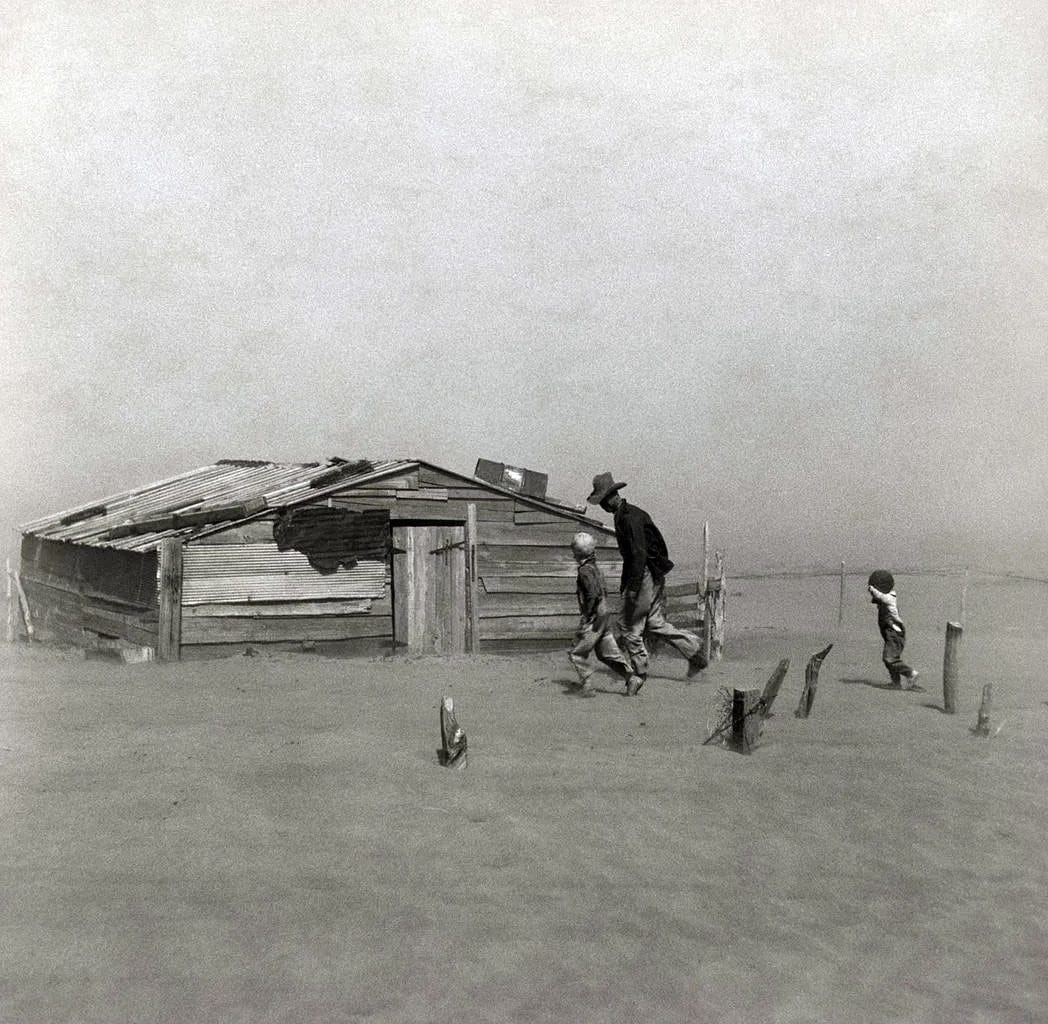

In the mid-1930’s, during the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration hired a group of photographers to document poverty in America. Known as the WPA photographers, they set the early standard for what would come to be known as documentary photography and would greatly influence both photojournalism and art photography. Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks and others set the stage for almost all that would come after, particularly documenting people living in poverty and environmental degradation. Yes, there’s too much of what’s now called poverty porn in documentary photography these days, but the best of it can still matter.

Counts hated art photography, or at least hated it when it was presented as photojournalism. After one class we had a little show in which we all got to present our best photograph. I chose one I took of flag girls at a high school football game. It was poorly focused and her face was overexposed with a hard light from the flash, but I thought it captured the absurdly deranged aspect of the spectacle. But Counts wouldn’t let me use it because it was “art” and you’ve never heard the word art used so derisively. Instead he chose a painfully sharp photo I had taken of an old woman with a very wrinkled face in front of a mirror that almost looked like it could have been a WPA photo. It got a lot of positive comments in the show, but even at the early stage I was rebelling against my upbringing. Counts was grumpy old grandpa. I liked and respected him, but I didn’t want to be him.

But more importantly, what I saw in those photos was the opposite of what Counts saw. Where he saw reality, I saw fakery. Where he saw falsity, I saw truth. I didn't like the photo of the old woman with the wrinkled face in the mirror because I basically manufactured it and did not see it as true. I was at an outdoor auction or flea market of some sort and there was a lot of furniture for sale out on the lawn. The wrinkled woman was looking at furniture and I asked if I could take her picture and placed her in front of the mirror, thinking I could make some statement about old age wistfully remembering youth. It worked, but that was not what was happening and I didn’t feel good about it. It was totally fake and I was using someone in a way that they probably wouldn’t approve of. Although the poorly focused flag girl with the weird light wasn’t sharp, on a more unconscious level, it caught the feel of the spectacle and I think accurately portrayed the nonsensical drama that she was a part of and what was going on around her.

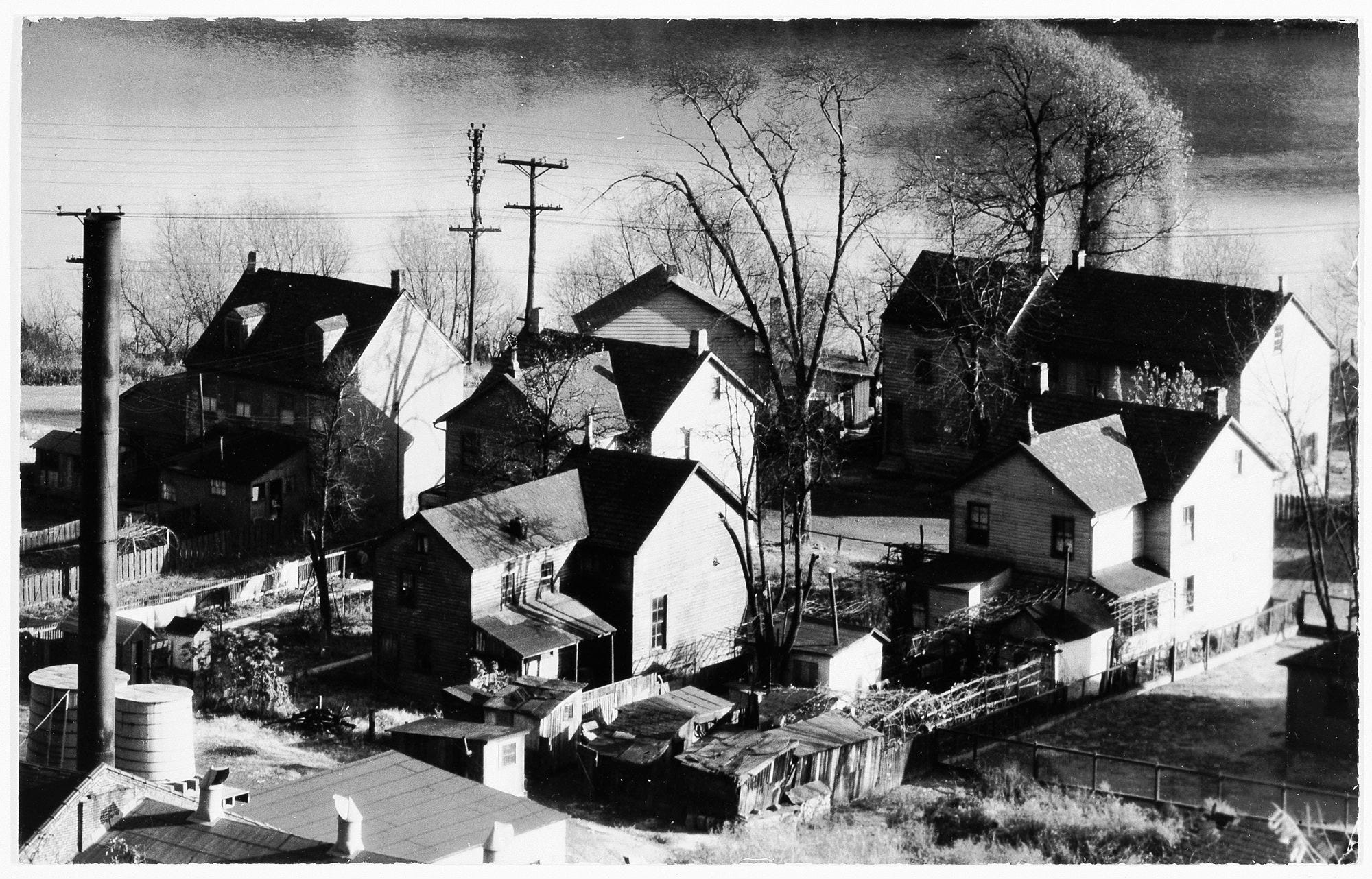

After the WPA, we studied a variety of early photographers, many of which did projects for Life Magazine, which was the standard for great photography for decades. W. Eugene Smith was one of Counts’ favorites, and was a big influence on me as well. Smith brought a more dramatic style to photojournalism than most of what had come before. The best WPA photographs were dramatic because their content was dramatic, but the shot was straight on at eye-level and developed without a lot of tricks. Smith brought different angles and advanced darkroom techniques to the game and produced some of the most iconic photos of all time.

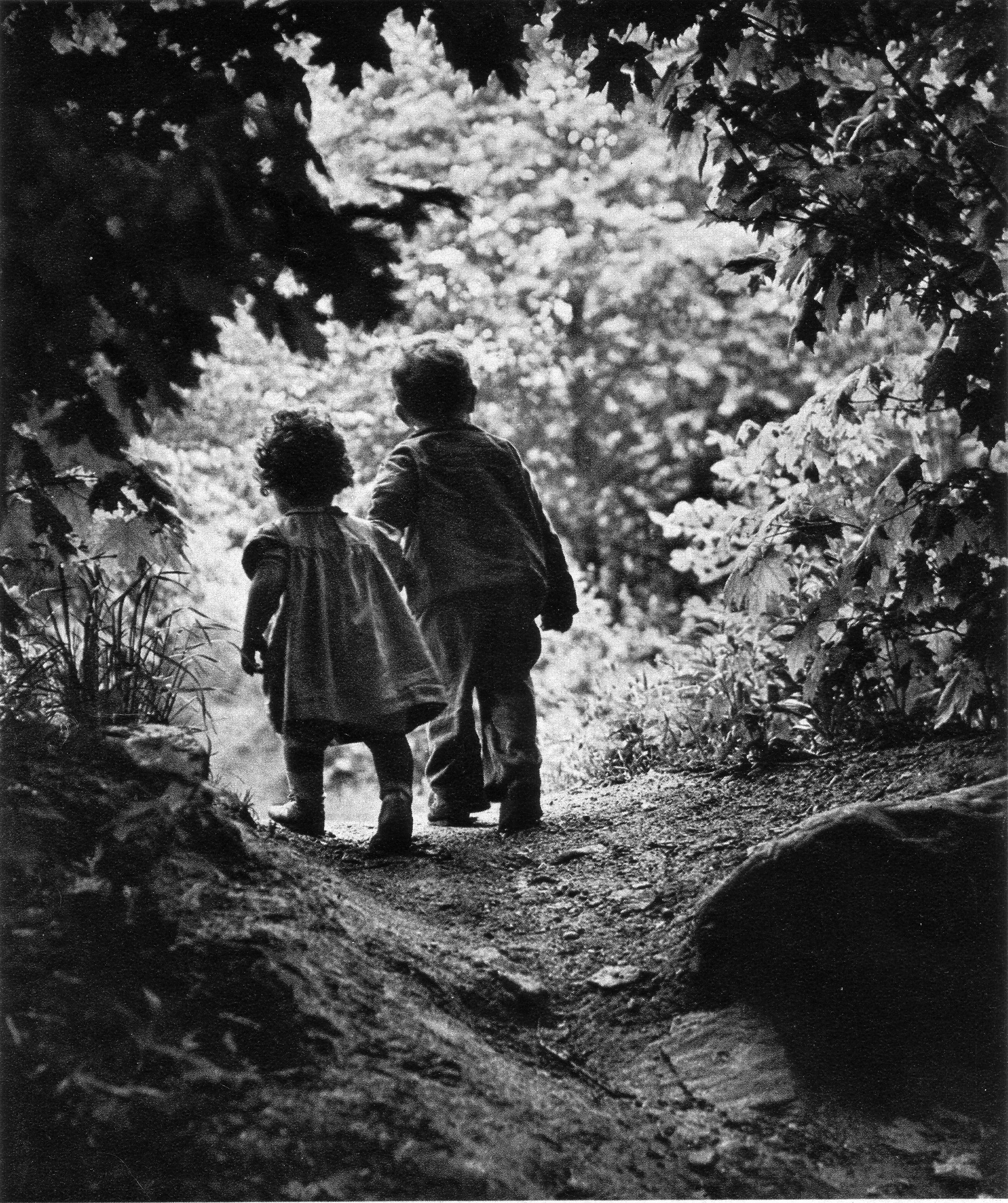

I have no interest in trying to reproduce any of Smith’s iconic photos in my own work, but I constantly try to reproduce the feelings I get from his best work. Not the same feelings of course, but some kind of feeling. Though I have to confess I try to take something like the Smith image below every chance I get. It’s one of my all time favorites.

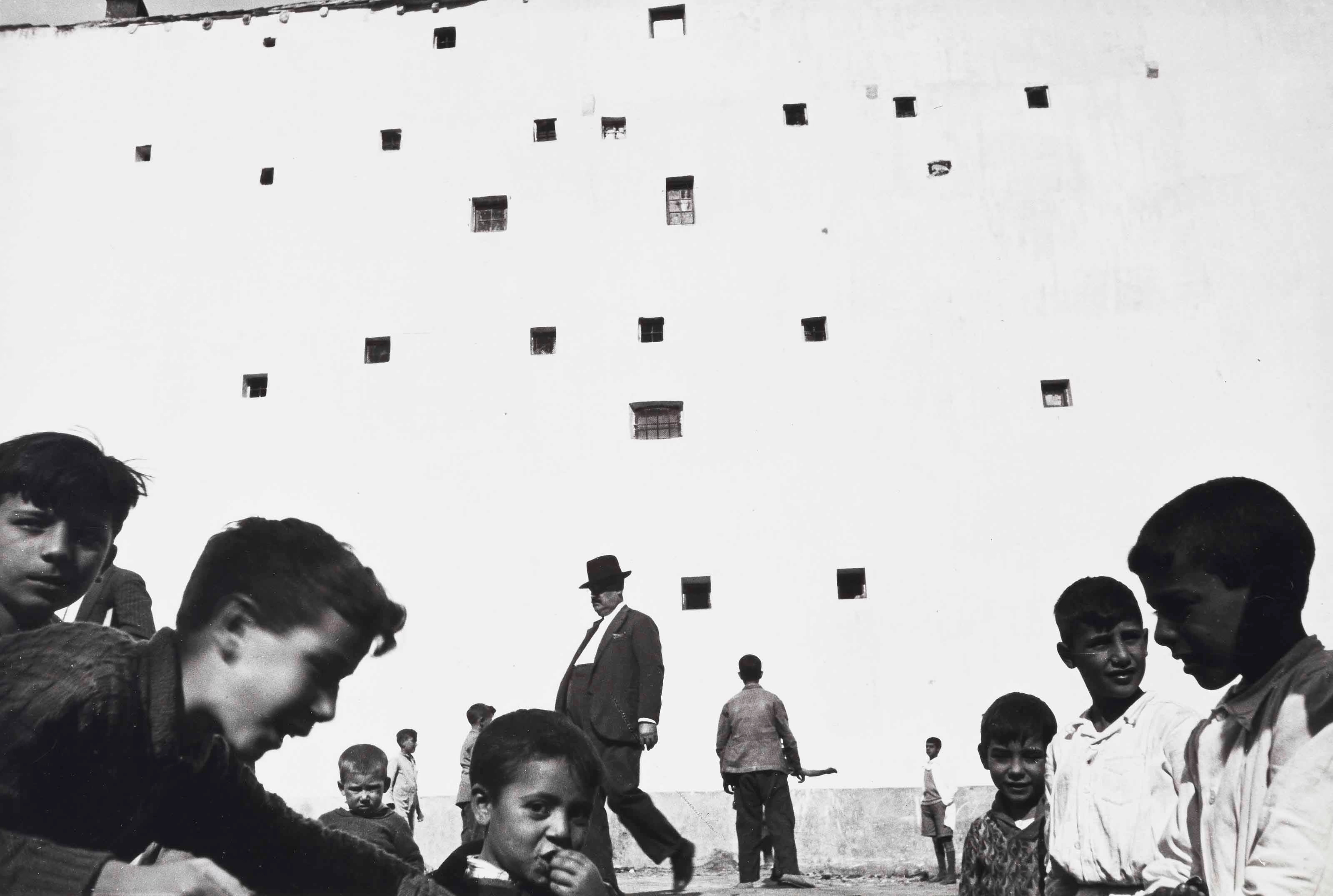

Henri Cartier-Bresson was probably the most influential early photographer and we saw and heard a lot about him in Counts’ photo classes. He pioneered what he called “The Decisive Moment” which is a kind of Zen-like method of capturing different elements in a scene at just the right instant to have the most dramatic effect.

The decisive moment technique continues to influence countless photographs and especially filmmakers. For filmmakers it’s relatively easy as they can visualize a scene and then place actors within a set and get a look that fakes a decisive moment. For photojournalists and documentary photographers it’s very difficult. There may be a few who just have the knack, but I think for most it takes a lot of practice and few will ever master it.

Of course I have practiced it, and continue to do so when the opportunity arises. It’s a lot of fun and sometimes results in a decent photo, but for me it’s usually more of an academic exercise. As you may have noticed, I usually bristle at the possibility that any of my work is flagrantly derivative.

We all see things that other people don’t’ see. The interesting pictures are the ones in which the artist is able to capture that which they see but no one else does. Then the viewer gets to see something new. Most images show us what we know exists. Great images reveal something we’ve never seen, even when it’s something we look at all the time.

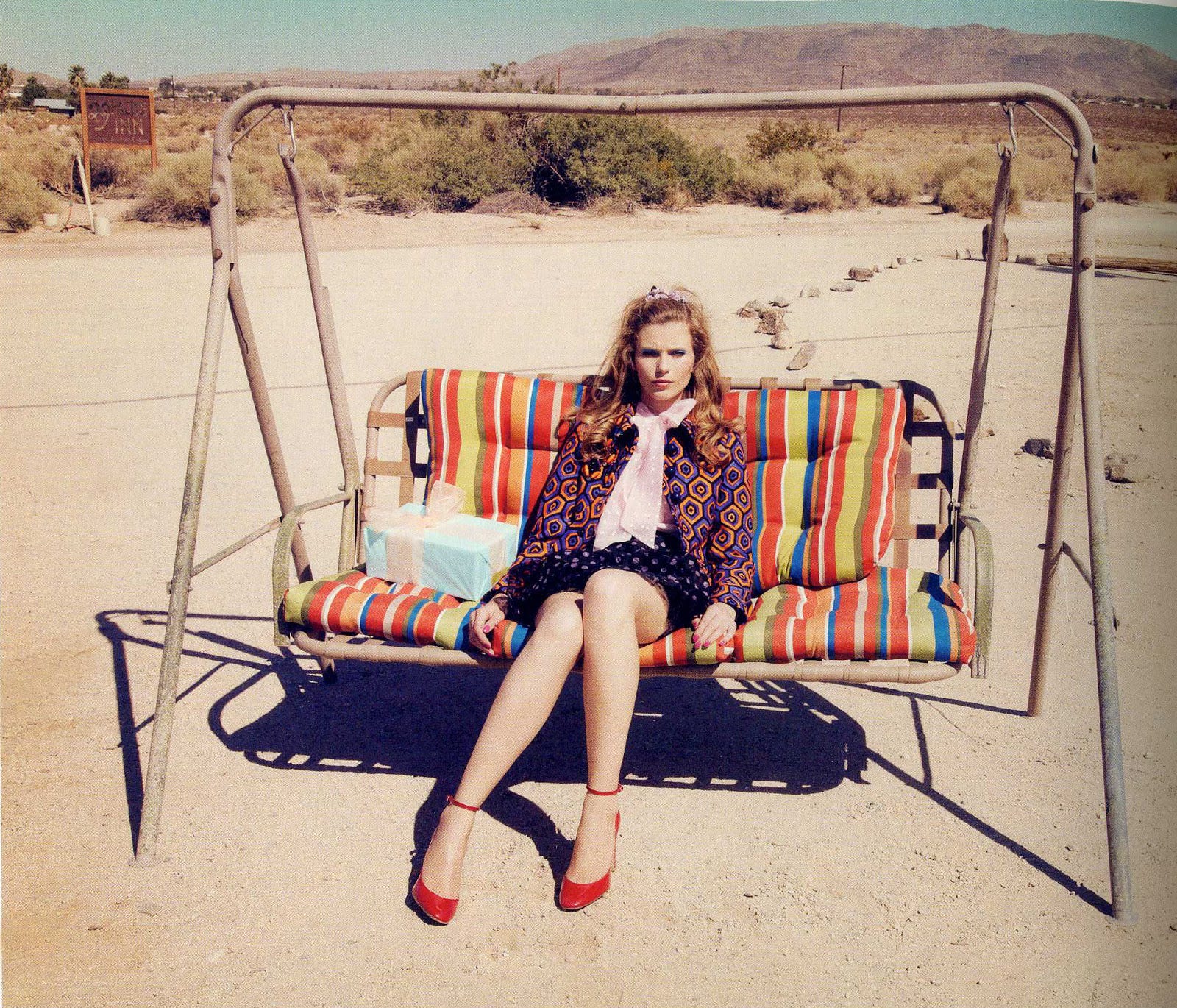

Which brings us back around to William Eggleston, an artist who bridges the worlds of j-school and art photography. Younger people may find this difficult to understand, and older folk difficult to remember, but for the early history of photography, color was considered declassé. Only black and white photography was considered serious.

That all changed in 1976 when Eggleston got a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Eggleston understood color like no photographer who had come before him and few since. His photos are mostly straight documentary at first glance but the color is also telling its own story beneath the superficial subject and composition of the image.

Counts introduced me to Eggleston way back when, which now that I think about it was only four or so years after the MOMA show, so he was up on what was going on in the wider world. But Counts was still of the black and white world and seemed to only teach color begrudgingly. Nevertheless, it made a great impression on me. Counts mixed the color assignment with the flash assignment, probably because the color film was so slow. Other than the wrinkled woman, it may have been the only time I got much praise during the class slideshow and critique. I took a technically difficult flash photo of a nice looking young woman by a lake at sunset with Kodachrome 24. I don’t think Eggleston affected my thinking at the time, what he was doing with color went over my young head, but I came back to it later in New York and he was, and is, a huge influence for my color photography.

I owe a lot to Counts. He taught photo history and he taught technique, but I think most importantly he taught attitude. History and technique, as well as seeing, are prereqs for being a good photographer, but attitude is what most often puts one over the top.

In Part II I’ll come back to Annie Liebowitz and where art school photography historically branched off from photojournalism, and I’ll discuss some more contemporary photographers and visual artists who have influenced me in painting and film, as well as my second great teacher after Counts, David Alan Harvey.